What is ‘feel for the water’?

A student recently asked me about the purpose of sculling.

I had just finished explaining to her how a simple scull begins with your arms extended forward. I demonstrated how she should arc her hands down and up as they move outward – as if her fingertips would trace a shallow ‘u’ shape. Then she’d retrace that shape inward.

An easy trick is to think “thumbs down, thumbs up.” When your hands move outward, both thumbs point down. When your arms move back together, both thumbs point up. You can even say the mantra to yourself as you perform the movement: “Thumbs down, thumbs up. Thumbs down, thumbs up.”

But what’s the point, she asked?

After all, you never use that motion in freestyle, which was the focus of our lesson.

What an excellent question!

Top U.S. sprinter Madison Kennedy conveys the sensations a swimmer feels in the water. Here she is at one of our clinics explaining the freestyle catch. I’ve been re-reading “The Science of Swimming,” James “Doc” Counsilman’s landmark 1968 book. At the time, it marked the fullest exploration of the sport through scientific principles and processes. Many of his stroke-specific techniques have since been disproven, such as the ‘S’ pull in freestyle. That idea, taught well in the 1980s, perhaps even the early 90s, has been universally abandoned in favor of the more powerful and efficient straight-line pull.

But his discussions about how fluid mechanics apply to movement in water are as true today as they were back then. (Or as true as they were 300 years ago, when Sir Isaac Newton formulated his Third Law of Motion, on action and reaction).

So are his observations about a swimmer’s perceptions of movement through a mass of liquid.

And that’s where we can get at the answer to my swimmer’s question:

What’s the point of sculling?

Think about a baseball player or a runner, Counsilman explains. They receive visual and even auditory sources of stimuli to assess how to perform their athletic motions. But the swimmer, “virtually enclosed in the medium in which he works,” must rely mostly on sensations of touch and body position for feedback.

Sculling is not a technical drill. It doesn’t mimic a portion of freestyle. It is meant to show the swimmer the feelings or sensations they will experience when they gain purchase on the water during the initial “catch” of a freestyle pull.

“The swimmer must develop the feeling in his hands for the right amount of pressure to apply during this part of the stroke,” Counsilman writes.

But feel for the water has broader implications. It applies to physical impressions across the swimmer’s entire body.

These sensations include water pressure on your head, shoulders and forearms. The faster you go, the greater the water pressure. They even include the sound of water rushing past your ears as you change speeds.

“Perhaps a great natural swimmer, possessing this nebulous quality of feel for the water, is simply a person able to perceive these multiple sensations, impart meaning to them, and adjust his stroke pattern accordingly.”

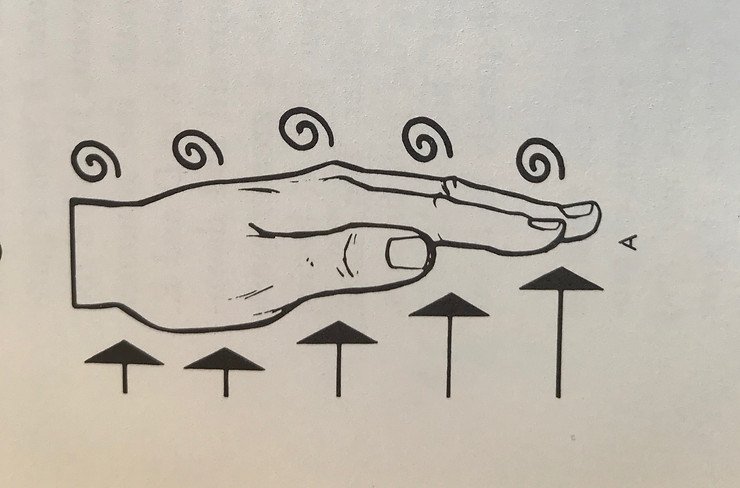

James “Doc” Counsilman used illustrations to demonstrate frontal resistance (arrows) and eddy resistance (swirls).

Doc goes on to speculate that such a swimmer may not even be consciously aware of that process. “He may be swimming entirely on impressions and sensations without knowing what he is doing in terms of actual stroke mechanics.”

That could explain why so many great athletes do not know much about the mechanics of their performances.

Most of us are not great athletes. Thankfully, we don’t need to be in order to apply these concepts to our swimming.

The point of sculling, I explained to my student, was to improve her ability to process sensations in swimming.

As Counselman observed more than 50 years ago, sculling is meant to give the freestyle swimmer mental impressions of “relative, constant pressure on the water as they move it backward.”

Time has undone some of Doc’s ideas.

But feel for the water, that nebulous concept, remains as tangible today as it ever was.